In a post for Writer’s Digest, Sarah Joverjun examines four types of unlikable characters and how to make them work. “Intentionally unlikable or not, protagonists who cause the reader to disconnect from the story can doom a manuscript,” Joverjun says. “You might need to dig a little deeper to figure out where the disconnect is so that you can address it in order to increase their investment in the story.”

Of course, you might decide this isn’t a problem. Sometimes, readers aren’t supposed to like your main character. Does anyone really like Tom Ripley or Ebenezer Scrooge? No, but readers remember them. Game of Thrones was filled with unlikable characters, and even those we rooted for were deeply flawed humans. But if you want to stick with your prickly hero, you need to lay the proper groundwork. “Your characters don’t have to be likable, but in order for them to be successful on the page, they do need to feel authentic,” Joverjun writes.

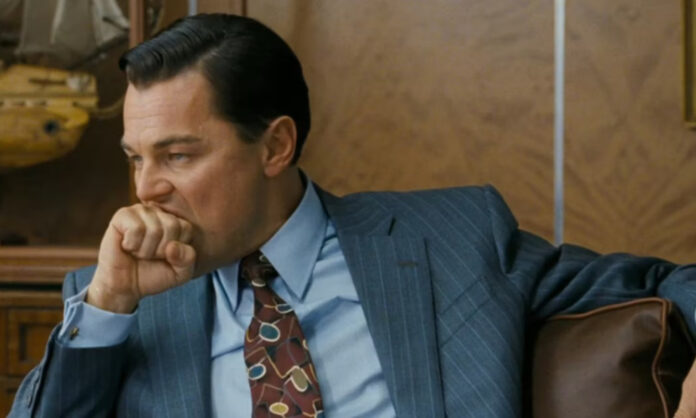

Joverjun examines a few types of unlikable characters, such as the hero with a rough exterior (Jessica Jones), the obnoxious jerk (Holden Caulfield), the morally suspect (Tom Ripley), and the outright irredeemable (The Joker). Depending on where your character falls on the spectrum, there are different approaches you can take to guide your reader into their story.

The Hidden Hero and Jerk Next Door can be softened by showing a compassionate moment with adds dimension to their personality. An irredeemable character needs to be appealing on some level, to prompt curiosity in your readers. As always, character is at the heart of your work. “Demonstrating motivation is a great way to develop three-dimensional characters,” Joverjun says. “Providing an explanation for why a despicable character makes the choices they do gives the reader a way to connect.”

Joverjun also says your character should amplify the unique elements of your story. Readers aren’t surprised that the characters in dystopian SF are morally ambiguous or when characters in a palace intrigue act ruthlessly to gain power (see Game of Thrones). We walk into those stories expecting these behaviors, and are ready for them.

Most of all, you don’t want your reader to feel indifferent to any of your characters. “Whether you’re writing Ted Lasso or Raskolnikov, focusing on character development is key to connecting with your readers and writing a plot that feels organic,” Joverjun writes. “Well-developed characters who make good on the promises of your genre while also amplifying the special parts of your story will forge an emotional connection with readers. And in the end, isn’t that the point?”