The last Pulse occurred in 5642, the one before that in 5632, the one before that in 5622, and so on. But each Pulse had come a minute or so earlier than the last, and one was left with the inevitable conclusion that they were increasing in frequency. We knew with the surety of atomic decay that the time would come when, at least for a while, they could be enjoyed annually. That is, until the frequency increased on the order of once every ten days, then once every ten seconds—and what would happen when they reached that undefinable pitch? For now though, it was enough that they occurred once every ten years.

The occasion of the most recent Pulse was savored with great delight among the younger folks, who possessed a near-limitless quantity of nerve in the face of such a great unknown. Most of these kids are too young to remember the insurgence of the ungodly black Slicks, who may seem tame now that they've all found their own tranquility wrapped in thick striation around and up the trunks of the nation's conifers (came the now-famous line "How about bark? Does anyone here remember the color of bark?" which was most likely never uttered at all) but were hellish on their arrival, oily and eyeless. And most of the kids do not remember, although their parents and their grandparents retell it with rising alarm in their voices, the tremendous outpouring of chunky red sand that came bubbling in great gobs out of the Pulse—and that had to be carted in teeming truckloads to the top of Mount Aura. There's a reminder of the occasion every winter when the summit burns bloody just before the onset of twilight.

And certainly none of them know the name Dr. Albert Difkind, although their horsehair strands—intercranial carbon nanotubing to you and I—could probably have the information in mind faster than you or I could look it up the old way. But ever since Difkind centralized the location of the Pulse using nothing more than a couple of Casimir plates, a light gas gun, and an ampule of pure sodium, kids gather at the Difkind spot on the night of the twenty-fourth and they wait. Sometimes they join hands and sing. Sometimes they sing without joining hands. Sometimes they tell crude jokes which they follow with crude laughter. Their method of enjoyment has changed, but the enjoyment itself is timeless. And even those who come away bruised and scratched have a happy and wonderful time.

But the real joy is in the weeks before, when the excited anticipation of whatever may arrive via the next Pulse is enough to start the heart pumping hurried hot blood through the extremities. Some of the older ones say that the time should not be rushed. That the days and weeks preceding the Pulse should be a time of reflection and quiet servitude to the senses. That the time before is merely time to suppress anxiety, for that is what strengthens the spirit. But try telling that to the hordes of kids whose behavior changes in the same way that dawn changes night into day—wholly, pervasively through the atmosphere. The Pulse cannot come soon enough for them. And I say let them be. They don't want their parents watching them anyway. If we stay far enough away, we can enjoy it with them. But I doubt we can enjoy it as much as they do, with aeons of life ahead of them, aeons of Pulses refreshing their world over and over again.

Dr. Difkind said there would one day be a way to keep track of the ever-changing origin of the Pulse. This footnote in his research was quickly forgotten (I don't need to tell you it was forgotten on purpose, do I?), but there is a movement—a small one, but a movement nonetheless—to resurrect Difkind's methods so that we may prepare ourselves more rigorously for whatever may arrive.

But I say, as my children do, that imagination is the only thing that is to be prepared rigorously, and that is all.

And so the time finally came after many dark weeks breathing frozen, smoky air. It culminated in a feverous, bustling last week of hurried meetings—as if the people greeting each other had only seconds to do so and would link up with them via horsehair at some later time—perhaps after the Pulse but not now, for heaven's sake, not now, we'll see you after the Pulse.

After the Pulse. There would be an after. That there had been so many afters since the first Pulse was cause for much joy.

And so my children went to the Difkind spot and joined the rest of the folks who stood around all wrapped up in layers like fat pastries. And as they waited, wind-blown, red-cheeked yet hot in their clothes, some of them sang, and the song caught on the way the tops of trees catch on to the song of a gale.

And the Pulse came.

As it had in the past, it started with a point. A dot of something in the few micrometers of space between the two metal plates. As the plates automatically collapsed on the instant amid a suppressed cheer, the dot swelled into a sphere until it reached the Difkind radius.

And what was to come through, came through.

An influx of briny-smelling things with many segmented legs, each rippling body the size and color of a walnut. Within minutes, a smell like a stray dog steeped in pickle juice pervaded the entire area. The crowd moved like a receding tide to allow them entrance into our world.

Some of the things expired quickly. Somewhere on our planet was a place capable of sustaining them, which is why the Pulse chose Earth over anywhere else. They would find that place soon. But it was necessary for the weaker ones to die off quickly due to their inability to adapt. Better for their future and ours. Some people in the crowd wept for them. Some of the more adventurous bared their arms and touched the frozen ground, inviting the surviving ones to scuttle up and nestle flat against steaming skin.

A few stayed and broke out in song. The rest dispersed and left the skittering things to find their way in the cold. That was the Pulse that year.

We welcomed our boy and girl back into the warmth and comfort of home, and after they'd unwrapped themselves they came to us. And we held them as they shook with sobs, and we didn't think of letting go.

The next night they downloaded some stuff about the ancient rites of Christmas. It was hard not having a horsehair strand to connect with them. And it was harder to consider the fact that some of the information might have been kept in mind and not shared aloud. But they told us some things about it. And we sipped our chocolate and laughed and cried around a ceremonial conifer, its trunk smooth and striped with oily black.

O Holy Night

Originally published online April 15, 2009

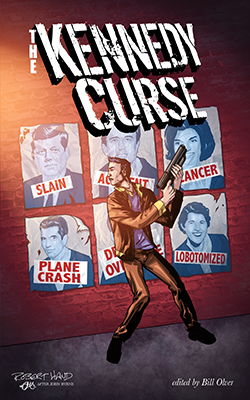

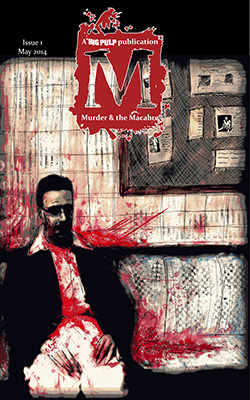

Paul Lorello is a freelance writer from Ronkonkoma, New York. His fiction has appeared in Big Pulp, Big Pulp’s Kennedy Curse and Black Chaos: Tales of the Zombie antholgoies, Membrane, and Pseudopod. In 2014, the Pseudopod podcast of Paul’s story, “Growth Spurt”, was chosen as the winner of the coveted Parsec Award for Best Speculative Fiction Story, Short Form. Paul lives with three quadrupeds and one biped and knows very little about everything.