Tall, slender, dark smooth skin, and those eyes! Clear, glittering, the iris that looked like crystal. Those unearthly eyes were what made Anyango a super-model. They flashed above jewelry by Cartier, above perfumes by Xikain, above lipsticks by ReFactor, and today, above a small snow-leopard cub for a wildlife conservation group.

Anyango hadn’t been there when her family was killed, back in Nairobi, near the stadium where the marabou storks roost in the roadside trees. Instead, the death-scene played itself out before her mind’s eye in a thousand variations, in clips from television news, from videogames, from action films. The tire marks where the red car careened out of control, crashed into a wall. The blood. The slumped bodies of her mother and father and little brother. The rush to the hospital, the frantic doctors who could do nothing. What she remembered was the gasp when her Aunt Mary took the phone, her scream, her words as she came over to Anyango who sat on the sofa, looking up startled from her Gameboy. “Oh, baby…”

Anyango was too frozen to respond. She stared at her Gameboy, pushing the same buttons over and over, her mind stopped. And the next day, Aunt Mary had screamed again. “Your eyes…Anyango, what happened to your eyes?”

It seemed strangely appropriate that the eyes she saw in the mirror were not the familiar dark brown, almost black irises. They glittered instead, like ice chips or diamonds shining where the light caught them. Anyango had not cried then or since.

An inexplicable pit had opened in her life where before there had been sunny savannah. Sometimes she dreamed about her family. She awoke a couple of times to Aunt Mary hovering worriedly above her. She looked at Anyango’s blankly glittering eyes. “Oh, baby…” she said.

Eventually, Anyango and Aunt Mary left Kenya, moved to America. Aunt Mary got a job with the Refugee Reception Center, dealing with people as baffled as she had been by this new world. When she managed to scrape together some money, there had been doctors’ visits for Anyango. The ophthalmologist sent her on to a series of specialists. Someone at UCLA got a paper out of it, a 19 year-old African female presenting with unusual crystalline structures contained in both orbits, no apparent effect on vision. No one could explain how the 32 degree Fahrenheit melting point of ice was compatible with the 98.6 degree temperature of the human body. No one tried. After a while, Anyango refused to see any other doctors. The diagnosis was idiopathic ocular aqueous crystallization.

It didn’t usually affect her eye-sight, but when it was hot, Anyango sometimes felt her vision blur, and a ripple of panic. She took to wearing dark glasses all the time, even indoors. She told people she had sensitive eyes. Maybe they thought she was being cool. Boys in baggy pants with silver chains around their necks tried to befriend her, but their talk of gangstas and hos and bitches annoyed her. She finished community college, and went to work for a storage company, a climate-controlled environment where they stored furs and other delicate and valuable things for the rich and famous and couldn’t-be-bothered.

In Cold Safe’s office, out of the heat of the Californian summer, she felt protected by the gusts of cool air whenever she opened a storage locker. Sometimes she even took off her specs, put them down on the desk. They were very dark. She had bought progressively darker ones as her fears had grown. Now, she could barely see through them except in full daylight. She carried an extra pair for indoors.

The doorbell rang unexpectedly. Clients usually called in advance to set up an appointment. Startled, she leaned forward to buzz the visitor in. Her glasses fell off.

“Fuck!” They were broken. She picked them up as the client entered. “Oh, sorry, Mr. Myrdal.”

“Max,” he said automatically. “Call me Max. I was on my way to the studio and thought I could drop this off…” He was carrying supermodel Sheliya’s fur coat for storage. As Anyango looked up at him, he stopped short.

“Anyango! Your eyes! You have simply amazing eyes! Why do you always cover them?”

“Thanks, Max,” she said with a courteous smile. “They’re sensitive. I just broke my glasses. Shall I take that fur?”

But he wouldn’t let the topic go. He invited her out for a drink. She politely refused. He suggested coffee instead. He called her home and spoke with Aunt Mary. Ten days later, he signed her with his agency, and Anyango said goodbye to Cold Safe.

They were very careful. Anyango removed her glasses only for the actual shoot. The hot lights were focused on a substitute, and Anyango stepped into them at the last minute. Max ordered even darker glasses for these sessions, so dark that Anyango could not see anything at all except when under the lights. When she removed them for the shot, the dazzle glittered off her ice and gave her a brilliant dazed expression that became her trademark.

Other agencies and models tried to copy the effect with contact lenses, with digitally altered images, even with surgery. Nothing was exactly the same and Anyango remained unique. Max added no one else to his Agency list, and let his other clients go. Anyango seemed never to go out of style, never suffer from over-exposure. Her eyes were likened to diamonds. Her dark skin shrugged off the abuse of the hot lights and the passage of time. She was timeless, ageless.

Timeless, ageless, and frozen. It seemed to Anyango that she saw no-one but Max and various camera crews, occasional marketing directors, a rival model or two, that she was alive only before the cameras. She had never been very good at making friends, not since Nairobi, not since the sparrow chatter of schoolgirls who did not know that Fate could swoop on them like a falcon. These days, the mystique of her super-model status seemed as much a barrier as her permanent dark glasses.

People had been good to her, and she was grateful. People like Aunt Mary, people like Max, people like some of her professors, even people like George Blair at Cold Safe. As a substitute for warmth, she practiced what she learned to call, in this America, random acts of kindness. A gift here, a note there, a new house of Aunt Mary’s choosing. It kept her tenuously connected to the human race.

Max, Aunt Mary told her, might be interested in more than a professional relationship.

“He let all his other models go to rival agencies, girl,” said her Aunt Mary. “That man is not hedging his bets. He goes out of his way to be nice to me, like I was family to him. A man does that for the future in-laws. I thought he would ask you out.”

“He did, a few times, but I was too tired. My eyes are sensitive.”

Today’s shoot was for Fauna Friend, a wildlife group. Anyango had waived her fees. Conservation was a cause important to her.

The session had gone on much longer than usual. She was tired. The snow-leopard cub had gone past curiosity, into playfulness, fallen into a nap, and awoken curious again. It had gotten away from its trainer a couple of times. She fondled the animal as it lay in her lap. It seemed about to curl up for another nap. It was really a delightful little creature. Her eyes closed to protect them from the glare of the lights, her mind drifted back to Kenya.

Instead of the endless variations on violent death, she recalled other cubs, lion cubs back in the savannah, where zebra grazed as casually as cattle in the Rift Valley. Clusters of shy giraffe stalking about the acacia-spotted plains. The protective mother elephant whose baby was always guided to the off-side, away from the vehicles and staring human eyes. Flying gazelles, and waterbuck and bunny-sized dik-diks that looked like plush toy deer. That had been their last trip together, just a few hours from Nairobi. The day they were leaving, they had come on the pride of lion lazing in the shade of a bush, two small cubs about the size of this one in her lap, playing with their mother’s tail. The animals ignored their car with the air of bored celebrities.

It was a long time since she had thought of it, thought of her family in any way but the car crash. Tears welled up in Anyango’s eyes. She quickly suppressed them, fearing what they might mean.

“One more shot and we’re done!”

She shook her head to clear it, then picked up the purring cub, held him under her chin, and stepped into the lights. Max removed her glasses, she opened her eyes, there was a click. She closed her eyes and Max put her glasses back on for her. She cradled the sleepy animal. The lighting tech killed the lights. With her dark glasses, she could see nothing. Max rushed to her elbow.

“Here, give the little guy over here.” He took hold of the animal to return it to its handler. “Ready?” he asked.

But before she could say anything, the cameraman exclaimed, “Oh, shit! Shit shit shit!”

Ten pairs of eyes turned to him.

“There’s something wrong! Nothing’s come out.”

A technician hurried over and fiddled with the camera. “Nothing much,” he said dismissively. “It needs a new chip. This one’s worn. I told you to replace it this morning.”

“But you never gave me one. It’s your job to keep the spares.”

“You should have asked…”

The Director took charge. “Stop squabbling, you two. Crew, stay where you are. Sorry, folks, we’re going to do this over. Jen, bring Fluffles to the make-up counter, let’s give him a quick brush. Max and Anyango, stand by. Shanika, we probably won’t need to adjust the lighting again, but stand by anyway.”

“Max, I can’t,” Anyango whispered. “It’s taken too long. We’ll have to come back tomorrow.”

The Fauna Friend president, watching the whole process anxiously, overheard and shook her head. “Anyango, please? We don’t have the budget to rent the studio and the leopard and the crew again. We’re grateful, really grateful, that you’re waiving your fees. But if we don’t do it now, we can’t do it at all.”

“I wish I could, but I can’t,” said Anyango. “I have sensitive eyes.”

The president sounded ready to cry. “We’ve spent a big chunk of our budget on hiring this outfit,” she said. “We can’t come back. We’d have to pay for it all again. And if we don’t have the shots, it will all be wasted.”

“I’m sorry,” said Max brusquely. “Anyango supports your cause. But she can’t do another shoot now.”

“It’s not just paying the studio,” said the woman. “This was the only day they had available this month. You don’t know what it took to pull this whole thing together on a small budget. The commercial is due to run early next month. We already paid for the space.”

“I’m sorry,” said Max.

“Wait,” said Anyango. She turned to where she heard the photographer still arguing with the technician. “How long will you need to retake it now?”

“Hey, everything is already set up,” he said. “We can do this in 20 minutes.”

“Let’s do it, then.”

Max looked dubious. “Anyango, it’s okay if we don’t. The contract specifies…”

“I know,” said Anyango. “But it’s only 20 minutes. They can’t afford to come back.”

“You’ll do it then?” said the president. She sounded jubilant. “Anyango, thank you!”

There was a whirl of activity as everyone took their positions. Fluffles allowed himself to be brushed and carried back to Anyango. She stepped into the light again. Suddenly, the cub raised a paw and batted her glasses off.

“Fuck!” she exclaimed, and bent over to pick them up. The cub scrambled out of her arms and escaped. Jen ran to intercept him as he scampered amidst the equipment. Too hot, too bright, thought Anyango, and she stepped quickly out of the lights. Even with her eyes shut, the glare was considerable. She raised her lids for a second, and realized her vision was blurring. She covered her eyes with her hand. Someone retrieved the glasses for her, but the lenses had popped out of the frame.

“That damn fool optician !” swore Max. “I told him unbreakable.”

“My outdoor specs are in my bag,” Anyango said.

Jen captured Fluffles and brought him over. Everything was made ready for the camera again, and Anyango positioned the wriggling little animal under her chin. The photographer took a succession of shots. Anyango could feel her eyes beginning to burn.

As soon as the director said “Okay, that’s it,” she handed Fluffles to Jen and turned to Max for the spare glasses. Max was right there, holding her bag, a large leather bucket full of impedimenta. She reached in, feeling around for her shades. Her eyes felt as though they were on fire. She put on the specs, and stumbled out.

Max put his arm around her, guiding her. His face was very close to hers. She could feel his warmth, and leaned into it.

“Come on, Anyango, I’ll take you home. Careful, there’s a step.”

It was cool and dark in his car. He had put in little curtains on the windows.

“My eyes, they really hurt. Did I overdo it?”

“Let’s get you home.” His tone was concerned, protective.

“I can’t go home like this; Aunt Mary will worry terribly…”

“To my place, then. And a doctor if needed.”

“Doctors,” she said bitterly. “What do they know?” She kept her eyes closed under her sunglasses.

The car stopped. Max came around and helped her out of the vehicle and in through the door of his house. He had his arms around her.

“Let me look,” he said. She put her face up for him to see her eyes, but kept them shut. He blew gently on her closed eyelids. “Let me look, Anyango.”

His voice was tender with suppressed worry. Impulsively, despite the burning, she pulled his face to hers, and kissed him on the mouth, hard. Even as she did so, it seemed the pain lessened. Eyes still closed, she moved back until she felt the couch behind her. She sat, drawing him down with her.

“Anyango?”

“Shh.” Her hands were fumbling around his collar now, down his shirt front. She put her hands behind his head, and pulled it toward her, and kissed him again. All the while, she kept her eyes tight shut. The pain was definitely ebbing. Her hands went to his waist.

“Anyango, are you sure?”

“Come on, Max,” she said impatiently, and at last he put his hands over hers, helping her.

Afterward, Anyango still dared not open her eyes, though she longed to look at Max. They no longer hurt, but were they well? She had to know but feared to find out.

“Max. Do you think I’m okay?”

He took her face in his hands. “Open your eyes, Anyango,” he said. She could hear apprehension in his voice. What would he find underneath her lids?

She looked up at him, trying to read what he saw in his face.

He had a strange expression. “Your eyes, Anyango. They’re different. Take a look.”

They were. Instead of the cold clear crystal of ice, the eyes in the mirror were dark and bottomless and full of stars.

Sensitive Ice

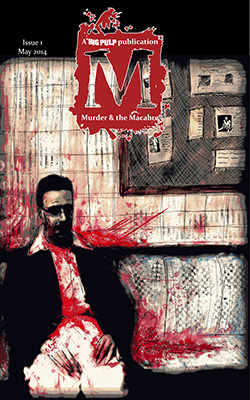

originally published in Big Pulp Fall 2009: On the Road From Galilee

Keyan Bowes is frequently ambushed by stories, and took the 2007 Clarion Workshop for science fiction and fantasy writers in self defense.Keyan’s work has been accepted by several magazines, including Strange Horizons, Cabinet des Fees, and Expanded Horizons, and is included in three anthologies, Eight Against Reality and The Book of Tentacles, as well as Art From Art. Her story “The Rumpelstiltskin Retellings” was made into a short film by Justin Whitney (Sea Urchin Productions). She is currently working on two young adult fantasy novels.