WELCOME TO MONKEYTOWN, WY

POP. 267

NO MONKEYS ALLOWED

1. No Monkeys in Monkeytown

The bartender at The Monkeytown Arms rubbed a shot glass over and over in his towel. Neither towel nor glass were clean. “We don’t serve your kind here.”

Orion stood straighter, stretching his vest tighter across his broad chest. The only thing keeping him out of the Fort Sill Nature Preserve for Greater Apes was this job, and he had to bring back his target this time, or he’d be locked up and sent back. “I’m looking for a chimp.”

“We don’t serve your kind here.”

Orion peered into the dark until his eyes adjusted, revealing an empty bar except for an orang female in the corner. “What about her?”

“Peaches?” the bartender asked. “She ain’t no monkey. She works here.”

Orion snorted. “I need to talk to her.”

“We don’t serve your kind here.”

“Don’t worry about it, Dave,” the orang purred. Her fur was shaved off except on her head, where it was piled high and decorated with silk flowers. She wore a scarlet and black lace dress that had been stuffed in the front to display what looked like human teats. She slid something from her table into a velvet bag and tied it tight. “It’s a monkey thing.”

“You be all right?” The bartender looked at Orion and didn’t see a runt, a hathscha who would never have his own troop. He saw a three-hundred-pound gorilla. Yet he reached under the bar regardless.

The orang tapped her fingers along her cheeks, then crossed her hands past each other. “You’ll know if I have trouble.”

The bartender looked away as the orang dragged her nails over the cloth of Orion’s shirt, digging them in lightly before removing her hand, a grooming gesture. “You have to pay.”

Her touch made his skin crawl, and he bared his teeth at her. “I don’t want your filthy body. I only have questions.”

She clutched the bag, flaring her nostrils. “I may have answers.” She swept past him, into a shadowed hallway and up the stairs. She smelled of fruit and flowers. “For a price.”

Something up in the rafters followed them.

Mi Tao led the pretend-human up to her room and let Absalom, her marmoset protector, slip inside the room before she closed the door. A small table on a single turned-wood pedestal sat in one corner. “Do you know the monkey cards?”

“I didn’t come here to have my fortune told,” he said. “I’m in a hurry.”

“They all say that.”

“I just want to find a chimp. General Regis. I know he’s here. He’s wanted for counterfeiting.”

“Who do you work for, the Army?”

“The Pinks.”

She raised an eyebrow. “Not much difference, anymore. Tell me, do you believe in magic?”

“Just tell me where he is.”

“Hell’s Canyon.”

“Where is that?”

She wagged a finger at him. “Come with me, and I will show you. But I warn you, you will see forbidden things. The government doesn’t want him because he’s counterfeiting. They want him because he can control the dead.”

“Don’t be ridiculous.”

She fluttered her hands toward her chest. “As you say.” She looked up at Absalom and whistled through her teeth. He dropped onto her shoulder, chittering at the hathscha, who stepped backward. She laughed. “You’re afraid of a little marmoset, are you? And you think capturing that chimp will be an easy matter.”

“What’s that he’s carrying?” The hathscha pointed at Absalom’s wrists, which were tied with small, thin leather packets.

“Poison needles,” Mi Tao said. “I always make sure assistance is near when I bring callers to my rooms. Are you certain you don’t want your fortunes read?”

He pinched his fingers together twice.

She stripped off her dress by pulling a leather tie down one side; it fell apart in two halves that opened like a clamshell. She scratched her fingernails into her sides, then hung the dress on a hook on the wall. Absalom climbed into her hair and started untangling the loops and throwing the flowers on the floor.

“Do you know why it’s called Monkeytown? Because only a few years ago, it was filled with all kinds of apes. Hathscha. They were here to make better lives for themselves, working at the silver mine. To live free of both the laws of men and the laws of apes. It was a kind of paradise, as long as you were willing to work. The mines were owned by a chimp named General Maxim, and everything in Monkeytown belonged to the apes.

“And then he died and left the mines to his so-called son, General Regis. Or so they say. Then the apes disappeared and disappeared, until there were no more monkeys in Monkeytown.”

“What about you?”

She didn’t answer him. “The wagons still roll up the trail, heavy with ore, and the few humans who live here grow rich. No one will speak of what happens in the mine.”

“I don’t care,” he said. “I don’t give a damn about those hathscha. We all have to prove ourselves. Justice is not my problem. Bringing back General Regis alive is my problem.”

“And when you work for the humans, you have to prove and prove and prove, and you will never have any troop to show for it.”

He bared his teeth at her.

From inside a wardrobe, she removed a leather jacket covered in long, orange orang hair and put it on. It would have been better if he had let her read the cards. She would have hinted at the truth, then. She closed a series of hooks and tied the laces at the top and bottom, and then she looked like an orang again. She hated playing the whore. But she had no room for pride, in serving the ronnok.

“Take them off,” she said.

“What?”

“Where we are going, you cannot wear clothes. You would be killed in a heartbeat. But the humans cannot tell us apart, when we do not play dress-up for them.”

“No,” he said.

She waved her hands toward her chest and led him down the back stairs, Absalom peering at him through her loosened hair.

2. Hell’s Canyon

Just past the gravel trail, rocks rose in painted, jagged teeth, row after row of them, like those of a shark. On the other side of the trail, a small creek ricocheted down a narrow crack to join a larger stream that smelled of cattle. The trail wound downward among the rock teeth, and pebbles skittled off the path to ricochet downstream.

“What is this place?”

“Hell’s Canyon,” the orang muttered.

His horse’s ears twitched as a larger piece of rock bounced down at them, hit the path, and clattered away. A cave gaped a few hundred feet up in the rock above them.

“What’s that?”

Her weight shifted behind him as she looked up at it. “Their Hill of Bones is past a dropoff at the back of the cave. It hasn’t been used for years.”

Orion shivered. Apes who lived in the traditional way piled their bones all together, the dead on top of the dead on top of the dead, until you couldn’t tell them apart. “Some of the human ways are better. To be buried separately, not all jumbled together.”

She fluttered her hands on his back, snorting. “You’ll never get a troop, thinking like that. Who wants to be alone, in death?”

The steep path followed the creek downward until they forded another small stream, the water only going up to the horse’s fetlocks.

Just past the water, the orang murmured, “Stop.”

Orion reined in, and she dangled off the horse’s side, dropped, and waved at him to stay. She knuckled quickly to the next turn in the path, hesitated, then went around a large rock. Orion shifted, patting the big horse, not quite ready to dismount.

She backed into view until she was past the rock, then softly knuckled back to him. “Tie the horse here, by the water. But don’t tie him too tight. If the dead ones find him, he should be able to run. And take off your clothes and walk normally, for ronnok’s sake.”

He shook his head and followed her along the trail. But he walked gently, making little sound, and took off his hat before he peered around the corner.

Around the turn, the landscape opened onto a hill made of gravel, topped with long, low wooden buildings made of weathered gray wood. Daylight shone through gaps in the walls, and some of the boards had fallen. The windows were open frames into darkness, the shutters fallen off on most of them. The creek poured loudly though a narrow pinch in the rock at the bottom of the hill, where a wood trough leading from a small gray building added what looked like a steady stream of blood to the water.

On the far side of the hill, gorillas stood motionless, watching a couple of wagons come down a gully. He would have thought them statues, but he could see flies buzzing around them. One of the apes turned from the far side of the hill and circled back toward them. The orang tugged at his arm, but he couldn’t move: the front of the hathscha’s face had been torn away, leaving pale muscle. As it came closer he could see red tears running from where the hathscha’s eyes had been, now black holes tinted with red. It reached the other side of the hill and circled away.

“Monkeytown Silver Mine,” the orang whispered. “Please. You have to stop acting human here. It will only get us killed.”

“It was dead,” he said.

She grunted. “Are you going or not?”

He watched the gorillas until the wagons had reached the stream and forded it, then took off his clothes, folded them, and put them in the horse’s saddlebags. He tried to buckle his gunbelt back on.

“That won’t do a thing to them,” she said. “You could burn them and scatter the ashes, and they would still have no rest. You will only reveal yourself if you wear those.”

Hands shaking, he put the guns in the bags with his clothing.

Damn this place. And damn that orang. She ran on all fours, her knuckles digging into the sharp gravel of the hill, toward a pile of rubble. He followed her, one eye on the gorillas helping unload the wagons, which looked to be full of rotten meat, trying to keep himself perfectly upright.

Mi Tao passed the dormitory quickly, hoping that any of the foremen who saw Orion would overlook him. But the low-lying areas of Hell’s Canyon turned quickly to dusk, even in the early afternoon, and they crossed the yard and reached the collar of the sump shaft without incident. She climbed the pile of rubble on the lee side, took one last look toward the dormitory—she felt eyes on her—and started climbing into the foul air of the mine.

Some of the cracks in the shaft were natural; some had been augmented with railroad spikes. She climbed past the first level to the fourth and stopped at the drift, then climbed further down, just far enough that Orion could feel the dark hole of the drift opposite them. Air blew the hair from her vest into her mouth and she spat it out as she gripped three spikes and scratched the edge of her vest with her other leg.

“Where are we?”

“General Regis is that way,” she said. “You’ll come to another downward tunnel. Go around it and over an old fall. It’s tight, but you can make it. Go to what looks like the end of the tunnel. Search the back of the tunnel until you find a couple of wood supports that are loose. Push them out of the way. Behind it is another tunnel, very thin. If you can make it through the old fall, you can make it through the tunnel. It splits to the left and to the right; take the left-hand tunnel only. General Regis’s offices are down there. Take him if you can, but watch out for more of those guards. If I’m not back by full dark, leave me.”

One hand moved toward his hip, then away. “What about you?”

“I’m not here to collect your bounty for you, hathscha.”

“Good.” Orion gathered himself and jumped overhead through the thin light of the tunnel, into the darkness. She heard a grunt and his paws scrabbling along the loose rock of the tunnel floor, then the padding of feet. She paused to listen: but no sounds of a fight followed.

She climbed downwards. Absalom shivered in her hair, and she tucked him inside the top of her vest. The walls went from dry to damp in only a few feet, and soon enough her foot broke through a layer of dead leaves, shit, and other garbage floating on the surface of the sump water. She jerked her foot back and tried to shake the wet, clinging things off her, but the more she shook, the more the garbage intertwined around her feet.

She reached—she had very long arms, even for an orang—until she found the next handhold, then let her lower body dangle as she tried to remember where the handhold after that would be. Something metal pinged against the shaft where she’d been a second ago. She groaned and dropped into the sump, then went limp, moving only enough to shift Absalom to her back and keep one ear free of the filth.

Above her, something chuckled, then scrabbled and slid on the gravel of the drift, where Orion had gone.

The tunnel was too short to walk upright in, yet when Orion settled onto his knuckles, he felt taller. The orang groaned and fell, splashed; he backed into the tunnel and waited. Someone chuckled, then gathered, inhaled, and leapt across the sump shaft. He waited. Its silhouette against the dim light of the shaft was small, agile, and the size and shape of a chimp as it slid across the look rock toward him.

He grabbed it, spun it against the wall, and clutched it by the throat. “Move and I kill you.”

“Orion?” the shaking voice asked. “That is you.”

He leaned forward and sniffed. “Sirena.” Then dropped her and stepped back. He knew her too well to think of her as safe. But she only sank down to her haunches and coughed.

“Why are you here?”

“I work for the owner.”

He smelled the lie more than heard it, but it wasn’t unexpected. “I’m here to bring him in.”

“Bring him in? Bring him in?” She slapped her hand on the wall and stood. “Never mind about that. Just you and me, let’s get out of here while we still can. I want to find a place without humans or apes. Without any lies.”

“What do you mean?”

“Less talk. More climb.” She stumbled toward the entrance of the shaft, and he grabbed her arm. “Leggo. You aren’t mad about that monkey I killed down there, are you?”

He bussed his lips. “No. I’m angry about Fort Sill. You betrayed me.”

“Let’s not talk about Fort Sill.”

“Why did you do it? I could have defended you from Merrill.”

“It’s not important.”

“I thought he killed you.”

She tried to pull away again, and he dragged her further down the tunnel while her legs scrabbled against the tunnel floor. “Don’t, Orion. Can’t you smell it?”

All he could smell was the foul water of the sump. He dragged her past the tunnel in the floor, which sucked down air with a low whistle, and to the rockfall. “You go first.”

She snapped her teeth at him, and he snapped back. “I won’t go back down there for you. I don’t belong to you, Orion. I’m not in your troop.”

He lowered her until he was breathing into her face, inhaling her breath. “Then it won’t matter what I do to you,” he said.

She slapped him, just like a human girl. A real chimp would have bitten him.

He grunted a laugh at her. “Merrill didn’t kill you and destroy your body. You left with him. You whore.”

“It was for love.” She wrenched away from him, climbed the pile of rubble quickly, and disappeared into a crevice.

“If you’re a female, either you’re part of the troop, or you’re a whore. Like that orang. It’s not love.”

Her voice echoed back at him: “You don’t know anything about it.”

He pulled himself into the rockfall with his hands. His head fit easily, but the rocks dragged against his shoulders, and he had to shove one ahead of the other in order to fit. He felt one sharp rock cut him open all down his side. The other end of the crevice was tighter, and he pushed against the sharp rock with all his might. He came free unexpectedly and rolled down the other side.

When he had looked into the darkness of the sump shaft, he had thought it absolute blackness. And then in the tunnel, he had known that the sump shaft was brighter, and the tunnel contained the real darkness. Now he looked for the glint of Sirena’s eyes and wondered if he’d ever see light again.

But even more than the darkness, it was the smell that made him hesitate. The sump and tunnel had smelled foul…but the smell on the other side of the rocks burned his lungs and made him sway on his feet.

He had smelled death before, at the Hill of Bones on the Preserve, back when he was trying to live two lives. At the human school, the boys had laughed at him when he had asked what a mother was and admitted that his sire didn’t play catch with him. So he had stolen a ball from one of the boys and asked his nukka to play with him. She’d chewed the ball to bits, but they’d played with rocks after he’d made her understand. She had lost her voice in an accident with their silverback, and could only sign sorry, sorry. He’d brought her a yellow dress with shell buttons from the trash pits, and she’d worn it every day while they’d played.

She had practiced with him for months, then thrown a rock at the silverback’s head, trying to kill him. He’d mauled her and left her for dead. When Orion had tried to drag her inside their hut, the ronnok had blocked his way, baring their teeth at him like animals.

And so he had dragged his nukka to the Hill of Bones, stopping at the bottom to roll her on her belly, raise a rock over her head, and smash it into her skull. He’d thrown her on top of the pile. The flies rose off the bodies but quickly landed again, covering them in shimmering blackness. He’d howled at her: Go away, then. You aren’t my mother.

But he’d buried her dress. Away from the silverback, away from the ronnok. Alone, in death.

That was the smell of this place.

Sirena hissed, “What are you doing? Aren’t you coming?”

Orion followed Sirena down the tunnel.

She grunted, and he heard wood shift. “Help me.”

He reached forward until his fingernails touched wood, which shifted as Sirena tugged on it. He found the edges of it—it was a full railroad tie, and he was surprised Sirena could move it at all—and pulled it away. The smell that came up made his arms go weak, and the tie tipped forward, thumping heavily against another heavy piece of wood.

“Orion!” Sirena gasped. “You almost hit me.”

“Sorry.” He picked up the tie again and leaned it back toward him. It stuck against the roof for a moment, but he tugged on it, and it fell toward him. He dragged it to the opposite wall and left it there. The foul smell continued to rise up. He took a deep breath of it. Another. Another.

“Does that make it smell better?” she asked incredulously.

“He’s dead down there, isn’t he? You left him for dead, like you did me. That’s why you want to get out of here.”

“You want to find out, start walking. He’s to the right.” Her voice came from behind and above him, as though she had climbed back into the crevice.

Orion moved two more railroad ties, one to the left and one to the right. The orang had been right: the tunnel was narrow, but not as tight as the hole through the rockfall. Ironically, he had to stand like a man (albeit with his head sunk down onto his shoulders as far as it would go) in order to fit into the right-hand tunnel, edging downward sideways with one hand searching the walls ahead of him and bracing his chest and buttocks against the rock. A rumbling sound came from the tunnel, but it was so quiet that he wasn’t sure whether he was hearing it or feeling it through the stone. After what might have been a few hundred feet or a mile of tightly-spiraled, downward tunnel, that he could see light, a kind of red mist that floated near the ceiling and cast shadows from his hand when he held it in front of him.

As he walked, the red mist filled more of the tunnel until his head was in it; it might have been smoke for all that he could smell with his deadened nostrils. The mist blinded him, but there was nothing to do but push forward until his knuckles knocked into wood. He grabbed for the board before it could fall and was lucky enough to catch the edge of it.

He edged closer. The end of the tunnel was a little wider, and he was able to squat under the mist, peering out the crack in the board.

In front of him was a kind of chapel, only without benches. A large cave had been carved out of the rock, and rows and rows of mixed apes sat under a deep cloud of red mist and waited. The apes had been dead a long time; he could see the white of bone under their hanging flesh.

They all faced one side of the room, where a pedestal had been placed to lift something red above the heads of the apes. It was too small, and surrounded by too much red mist, and his eyes smarted too much, for him to make out what it was, but it seemed to be waving at him. His ears rang, and he could almost hear voices.

His nukka chattered on in grunts and sign language about hot tea. Sirena told him to be quiet, or Merrill would find her and kill her. His own voice, telling her that he would protect her, no matter what anyone thought of it. Sirena saying—she had never admitted it, in life—that she wanted a lover, a human kind of lover, someone who would love her and her alone. He told her he loved her, would always love her. She answered that she belonged to Merrill now, and that she could not speak to him again. It was what she should have said, instead of faking her own death rather than tell the truth.

In the ringing of his ears, she screeched at him. I thought you’d understand, that of anyone, you’d understand. To be able to take a lover before you’d killed a hundred hathscha. To live without such murder on your hands. To be able to live and breathe and love without the weight of the ronnok at your throat. Freedom.

The ringing changed. The power to never have to obey the humans again, or the apes. The power to live freely. The power to become one who is served, rather than one who serves.

The board fell from his fingers, but the apes didn’t notice. He took another step forward. Another. The mist surrounded him, soothed him. Freedom.

3. The Red Monkey

After she climbed from the sump water, Mi Tao stroked the top of Absalom’s head. His breath whistled in and out of his mouth in tiny, quick gasps. She breathed onto him, and his chest fluttered, then returned to panting. The smell coming from the tunnel was less, even though its floor was only inches from the level of the water in the sump. Shit and garbage curled in dried lumps on the floor, which shook slightly underfoot.

She brought him to her lips and kissed him, then tucked him into the top of her vest again. She walked forward through the dark, the tunnel narrowing around her, until she reached a blank wall. She stopped to sign a spell, and it surrounded her and Absalom. The red mist would do nothing to them for a long while, although the sooner they were out of it, the better. Luckily the hathscha would be walking tunnels that would take him nowhere near it.

She said another spell, and light shimmered underfoot. She walked toward the rock wall, and it slumped before her, rolling off the sides of the spell, solidifying in drips. When she was through, she released the spell and was bathed in the red glow of the mist. The tunnels rumbled so loudly that her ears ached almost immediately.

Some of the red mist poured out of the hole and up the tunnel, but not too much. She crouched low under the mist and looked from left to right. The tunnel sloped downward to the right, so she turned that direction, the red mist filling the tunnel until she could see nothing. But the dreadful rumbling that filled the tunnel suddenly became louder, and she reached out until she found the opening in the tunnel wall, the one that led downward into the pit.

She had never been this far before. She’d never dared. She paused a moment in honor of the hathscha, who must have drawn the guards upwards to him, for there were none to be heard in the tunnel now. Then she slid over the edge of the opening and dangled down to what must be there: the handholds for going downward into the pit.

She climbed down until she was past the mist and could see the pit fully. It stretched downward for another thousand feet, and she swayed. The bottom of the tunnel was filled with a red haze of stone chips as the machine at the bottom ground downward imperceptibly but inexorably. Pipes led down to the machine, or perhaps led upward. The great machine itself was colored red with dust and so loud that she couldn’t hear it any more, only feel it. She stuffed some of her hair into her ears, and more of it into Absalom’s, then continued to descend slowly from handhold to handhold.

The hathscha under General Maxim had built it, engineers who had fled service at mines to the East. Far better than anything a human could have made. Had General Maxim known what he would find when he started digging here? Probably he had believed nothing of the legends, only in the silver.

The handholds ran out before she reached the machine; she could easily take the fall, but she couldn’t see how she could get back up again. She would have to find a different way. She watched the machine for a time, then dangled off the last spike and dropped.

At the top of the machine was a door that opened by means of a metal wheel. She sealed it behind her as tightly as she could, then pulled the hair out of her ears with relief. She waited until her ears stopped ringing, then pressed her head against the bare metal of the next door. She heard nothing, and loosened the door.

As soon as she had opened the door a crack, Absalom slipped through. She waited a few moments, and then his tiny head reappeared as he chittered at her.

The other side of the door held no threats she could see, but contrasted with the bare metal of her entrance: red velvet carpet covered the floor and the bottom halves of the walls, and golden wallpaper the rest of the way up and across the ceiling. Crystals connected with gold wire shivered under gas lights turned so low as to be nothing but a shimmer—but after the tunnels, a shimmer was all Mi Tao needed. Red velvet chairs and couches filled the narrow lounge, with a gold-colored runner down the middle, leading to the next dogged door.

The machine shuddered, and glass clinked from a small cabinet along the wall, behind a short table. Behind the first two cabinet doors were decanters of liquor in a divided tray, each bottled separated from the next by a velvet box. One of the bottles had broken, and the bits of glass— dry but still aromatic— jostled against each other. It was only then that she noticed the room did not smell of death.

Behind the third door was a safe. Her hairs stood on end, and she hissed between her teeth. Absalom ran up to look, but she held him back with her hand. The door of the safe was loose on its hinges and groaned when she opened it.

The top shelf of the safe held a stack of stiff envelopes full of paper, and she was sure that if she opened them, she would find all kinds of treasures from the human world; humans were fond of putting their treasures to paper, as though to write a thing down was to give one power over it.

But she was more interested in the gold collar in the larger, bottom part of the safe. It was made of fine, small links that her nail couldn’t scratch, and was sized to leash a marmoset. She took the collar out and wrapped it around one wrist.

The machine shuddered, and the door of the safe moaned as it swung on its hinges. She pushed it closed, but it was locked open. She heard another moan, this time from the other end of the room: the other door was opening. She backed behind one of the chairs, but not soon enough.

General Regis screeched, “You!”

“General. If that’s your name.” She moved to the center of the carpets to give herself more room for her spells and raised her arms to sign. He was close enough to smell, and that meant he was close enough to attack. She signed the spell even as he leapt at her, and the rustle and glint of magic rushed at him.

It should have pushed him back, but instead burst like a bubble. He landed on her and went straight for her throat. She pulled her feet up under her, braced them on his chest, and shoved, whipping his head back before his teeth could close, but she still felt the hair on her neck rip away. The chimp’s face was ugly with scars, and he wore a red-coated uniform, like a member of royalty rather than a military general.

They circled each other around a short table. He swung at her, she dodged back.

“You’re no whore,” he spat. “You’re here to steal the Red Monkey for the ronnok. But why now? Did Sirena tell you?”

She dodged another of his grabs. She was big for a female orang, but his arms were still longer. “I’m sure she didn’t mean to. But she can’t resist her little hints. She talks almost as much as a male with a whore.”

He bared his teeth at her.

“She didn’t tell me you could resist magic, though,” she said.

His hand reached across his chest for a moment, and she saw that his breast pocket bulged. A protection charm of some kind that would likely protect him from physical as well as magical harm. She backed away from the table toward the cabinet, and he followed her, hoping to back her in the corner, rip out her throat, and piss on her corpse, no doubt. But over the cabinet was a crystal chandelier, and it shivered with more than just the shuddering of the machine as Absalom hid in it.

“A particular talent of mine,” he said. They could both smell the lies on each others’ fur; it was just a matter of finding out how much was a lie. He swiped at her, and she stumbled over one of the chair legs, and he caught her vest, which was as well built as a second skin. He pulled her closer as she dug her nails into the chair, her arms stretching wide.

He yanked her away from the chair and she went flying toward him. She clawed the pocket open, and whatever had been in his pocket went flying, even as he clutched her close to bite: “Now, Absalom, now!”

General Regis shook his head and stepped backward. She didn’t know whether the poison would be strong enough…or weak enough. She supposed she owed the gorilla a chance to satisfy his idiot dreams of somehow becoming the equal of the humans by bringing General Regis to “justice.” As the chimp stumbled and went down, she grabbed one of the full bottles of liquor from the cabinet, and hit him across the back of his head. He slumped forward over his legs, then leaned to the side, drooling blood onto his carpet.

Mi Tao raised her arms, and Absalom jumped into them. “You precious thing,” she cooed at him, scratching him delicately. After a few seconds, he jumped down to the floor, an pointed excitedly at something small and red lay smashed into the carpet. When she examined it, it was a tiny red paw no bigger than Absalom’s.

4. The Price of Freedom

Metal pinged off the wallpaper, and Mi Tao dropped to her belly beside the table. A shadow lingered on the other side of the far door.

“He called you a whore,” the shadow called.

Absalom crawled up on her shoulder, and another dart pinged, this time against glass. No telling where it had bounced off to.

“You’re here to steal it, aren’t you?” The shadow moved, shifting her weight. “Trust me. You don’t want it. You don’t know what it does to you. If you want to keep the power, you have to keep killing. Otherwise they turn on you.”

Mi Tao stroked Absalom on the head to keep him calm, but he jerked away from her hand and ran under a chair. She sent him a silent wish for good fortune, then started to crawl toward the opposite chair, trying to get closer to the door. A needle buried itself in the carpet just past her side.

“The digging,” the shadow continued, as though she hadn’t just tried to kill her, “he keeps digging because he’s greedy. I left Orion in the chapel with it. He’s dead already. He attacked me. He deserved it. He’s just a stupid hathscha.”

Suddenly the assassin scrabbled away from the door, screeching in fear. “Don’t hurt me! Don’t hurt me! Save Orion! We have to save Orion! I can lead you to him.”

Absalom trotted back to Mi Tao across the carpet, looking smug. “I think you scared her, love.” He ran under her hair, chittering contentedly. To the assassin, she called, “Lead the way, traitor.”

“I’m not a traitor!”

“And I’m not a whore.” Mi Tao bent over and picked up the red paw from where it had fallen; she tucked it into her vest and ducked through the other door, half-expecting to be poisoned or hit over the head as she came through. But the chimp only led her out of the ship and over a series of pipes that carried cold water to the machine and hot water away.

“It’s magic, the way this machine works,” she said, jumping across pipes.

Mi Tao hissed as her feet hit the hot pipe. “No. Just engineering. General Maxim’s apes did this, you know, before Regis came here and killed him and ruined everything.”

“I didn’t know.”

“You knew.”

They reached the top of the pit, then crept along the hallway until they reached an arched doorway. Inside, hundreds of apes swayed back and forth as they watched something small and red on a pedestal on the other side of the room.

“There,” Sirena said, pointing into the crowd. “He’s there.” Mi Tao couldn’t see him. Suddenly, the chimp shoved her into the room and screeched. The great dead apes turned, and Sirena backed away from the room. Mi Tao signed a curse, and flung the power at the chimp, who screeched and ran for all she was worth.

At least that was done. She signed a spell of protection, and light flashed under her feet in a dappled pattern, like shifting sunlight through branches. The dead ones pushed toward her, their eyes covered with a red film that dripped like tears and crusted on their faces and fur, but the spell turned them away, and Absalom hid inside her vest, shivering. He had never trusted her talents, preferring to rely on quickness and sharp needles. Sparks rose from the rock where her spell touched it, and the apes’ fur smoked where they tried to touch her.

She pushed forward. She was a quarter of the way through the apes. Halfway. Three quarters. The spell began to dim beneath her as ape after ape threw himself at her, trying to wrestle her to the ground. Her years of training would come to nothing: she might be able to reach the Red Monkey, but she could not return with it.

She could destroy it—it was only a statuette, after all, and could be broken—or she could make a life sacrifice and take on its power for a time. But as the assassin had said, it was a kind of power that continuously needed to be fed, and she wished to leave the burden and wisdom of using it with the new, united ronnok, the convocation of female elders who would bring the mixed races and overthrow the humans. It had been her nukka’s dream, and it kept her power focused when she should have been broken and shivering with exhaustion.

She reached the Red Monkey. She couldn’t think. The only other living thing inside this horrible chamber was Absalom. To destroy the idol was to damn her people to slavery. To sacrifice Absalom was unthinkable.

She reached up and grabbed the idol with her long arms, pulled it down, and flung it on the floor. It smashed with the sound of any piece of stoneware hurled in anger. One moment it had embodied power over death; the next, it was shards of red on the floor. Within a breath, the mist disappeared.

The apes collapsed. She had failed. She had worked for years to obtain this power for the ronnok, and then she had destroyed it over a stupid monkey. She scratched Absalom on the head, kissed him, and promised him fresh fruit. They would travel to Spanish Mexico and disappear in the jungle. They would be gone for months before the ronnok knew what she had done.

She picked up the pieces and wrapped them in the cloth covering the pedestal, then tied them into a bundle. She would find a way for the pieces to be given to the ronnok somehow. A way that didn’t involve facing their wrath. Even carrying the bundle, she felt lighter. She felt like laughing.

She picked her way through the rotting dead until she found the hathscha and nudged him with her foot. “Wake up, you. I know you’re only sleeping.”

He opened his eyes. “What happened?”

“You were turned to one of the dead by the statue. I smashed it.”

“What happened to Sirena?”

She had sent him into the caverns to die. She owed him many things. “She came back to save you…she was lost in the fighting.” He might not smell the lie in that.

“The General?”

“In a mining machine below.”

His upper lip shuddered as he waited for the worst. “Dead?”

“Knocked out. I knew you wanted him.”

The hathscha rolled onto his side, then pushed himself up on his knees. “Show me.” He wiped his face, smearing the trails of red tears across his cheeks.

The orang carried a small, rattling bag with her. “What is that?”

“A souvenir.” She led him without further comment as the rumbling grew louder, until his ears felt as though they would bleed, until they stood at a narrow window looking over a vast pit. She tied the bag around her, then started descending on a series of pegs, then jumping lightly onto a sturdy metal pipe.

They worked their way downward. The pipes held, although some of them leaked after he had passed.

The machine ground on, kicking up red dust that looked like blood. She brushed away a layer of dust and rock chips from a small hatch, opened it, and went inside. He could barely follow her. She stood before a second door. “I left him in there.”

He pushed open the door, then leaped through it. Before he knew what he was doing, he swept Sirena into his arms and buried his head in her neck. After a few seconds, he noticed her struggling and let her go.

He let his eyes fill up with the sight of her, his nose with the scent of her. She screeched and hurled herself at him, attacking. He stepped back from her. “Sirena…Sirena…it’s me. Orion.”

He stumbled over something and looked down. Shock almost knocked him from his feet. “Merrill,” he said. The chimp was dressed in a silly uniform of some kind, with a red coat and gold braid. His face was covered with scars that reminded him of the wanted posted the Pinks had given him of General Regis. But surely it was not him. Sirena bent over him, cooing at him, poking him, trying to get him to wake up.

“What did you do to her?” he asked.

Mi Tao, still on the other side of the door, turned and started to climb up the ladder to the door outside. In a second, he pinned her face against the wall of the machine. “What did you do?”

The orang gasped, and he dropped her. She pulled open the top of her vest. Her chest was covered in blood; her little pet marmoset had been crushed between her and the wall.

“Absalom,” she whispered.

“What did you do to her?” He grabbed her head and made her look at him.

Her eyes were filled with tears. “She tried to kill me.”

“What did you do?” he roared.

“I took away her mind.”

He backhanded her, and she landed against the ladder and fell down. He picked her up again; she was murmuring something as he hit her again.

Suddenly, something horrible grabbed him from behind and wrapped fire around his throat. He couldn’t breathe. He raised his hands to try to tear the thing away, but it scrambled through his fingers and pulled harder. Blackness surrounded the outside of his vision, and he sank to his knees, then rolled onto his side.

“That’s enough,” the orang said, and it let go of him, scampering toward her, crawling up her shoulder, and hiding in her hair. Something red, trailing something long and gold.

She reached into her vest and handed it something small and red— the same color, actually— and it chittered in approval.

“Don’t touch me again,” she told Orion. “I owe you nothing.”

He tried to croak out that she owed him for Sirena, but nothing would come out, and he couldn’t force himself to move. She climbed out of the hatch in the roof and was gone.

He lost consciousness for a time. When he awakened, he picked up the General and a bundle of manila envelopes from a safe hidden inside the liquor cabinet and carried him upward inch by slow inch, trying to keep Sirena from hitting him with rocks as she tried to defend her mate.

He had to get the General back to the Pinkertons.

He knew no other way to the surface, so when he reached the strange temple, he walked through it to the tunnel entrance, trying not to step on too many of the dead apes around him. All males. All hathscha of every species. They had searched for a better life, away from the humans and the ronnok and from murdering each other to earn their troops. Apes caught between the human and the ape worlds, accepted by neither, looking for purpose and work and peace.

He brought the General out to the last of the twilight and laid him neatly on the ground, straightening his clothing. Sirena helped him, cooing and patting his fur. For this, she had betrayed him. And Merrill, in turn, had betrayed this little paradise and taken it over for greed. Not for her.

He found a rock the size of his head and smashed it into the General’s face until it was gone, despite Sirena’s screeches.

He dressed, put his guns on, and tried to get her to come back with him to the horse, but she ran away into the shadows.

It would be a long ride to Fort Sill. But he thought he might be able to make a caravan of it on the way back, if he sold some of the stock certificates in those envelopes. He’d come back with an army and some lawyers showing that he owned the place from top to bottom. General Orion.

And then they’d take down that damned sign.

No Monkeys in Monkeytown

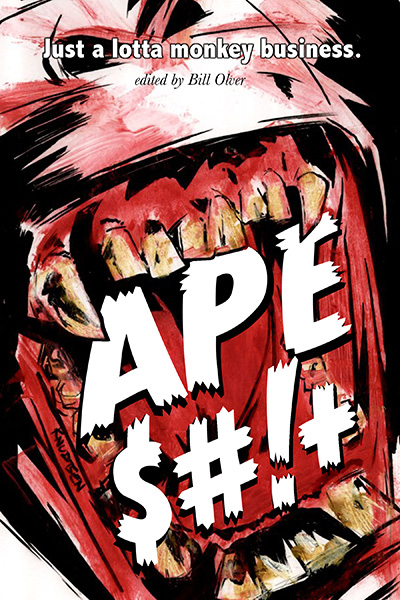

originally published in Apeshit

DeAnna Knippling is a freelance writer and editor in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Her first book, Choose Your Doom: Zombie Apocalypse, was released in November 2010 (www.doompress.com). She was recently published in Three-Lobed Burning Eye, Silverthought Online, Crossed Genres, and Nil Desperandum. She received an honorable mention in Best Horror of the Year, Vol. 3, and has been published in Big Pulp multiple times.